sculpies // Shutterstock

The U.S. is short about 4.3 million homes, according to recent estimates from Zillow, a key reason buying a home has gotten more expensive. But the simplest solution, to build more houses, has a flaw—there’s no one to build them. That’s because homebuilders can’t find construction workers.

“In the wake of the Great Recession, the residential construction industry lost 1.5 million jobs. Tens of thousands of homebuilders went out of business. The workforce really fell,” explained Robert Dietz, chief economist at the National Association of Home Builders. “Building that kind of infrastructure and human capital takes time. Years later, we’re still clawing our way back.”

With fewer workers, building homes is taking longer than ever. In 2022, it took an average of 8.3 months to build a single-family home, the longest since the Census Bureau began collecting data in 1971. And as the saying goes: Time is money. So even with stagnating wages, it costs more to build a house—costs that ultimately are passed on to the buyer.

Even as the housing market cools and fewer people are buying homes, the sector needs to add 723,000 jobs per year to keep up with demand, according to an analysis from the National Association of Home Builders. In the first half of 2023, homebuilders added 2,000 new workers per month on average.

In other words, builders must bring on 30 times the number of new construction worker hires than the current pace. Builders are trying; so far this year, there have been 350,000 construction jobs available every month on average, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey.

Stacker looked at the state of employment in the home construction industry and reasons for the shortage using data from the Labor Department, the National Association of Home Builders, the Department of Education, and other sources.

![]()

Aging out

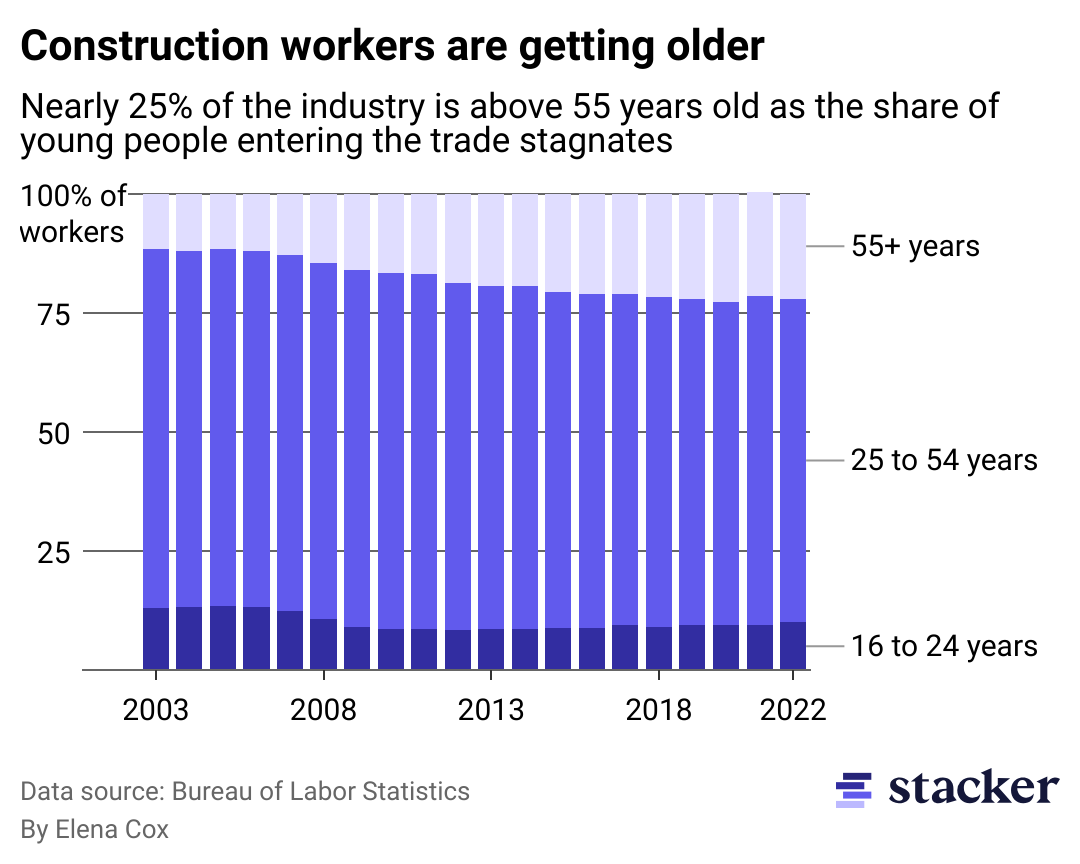

The average age of construction workers has increased as fewer young people enter the workforce. As those workers retire, there aren’t enough people coming up behind them to take their spots. In 2022, nearly a quarter of construction workers were over 55.

This trend is largely due to the growing stigma of manual labor and the emphasis on college education for success.

“Even an aged plumber, someone 60 years old, where his or her dad was a plumber, has become somewhat brainwashed into thinking their child needs a degree,” said Ed Brady, president and CEO of the Home Builders Institute, an educational nonprofit organization. “We’re going to run out of people.”

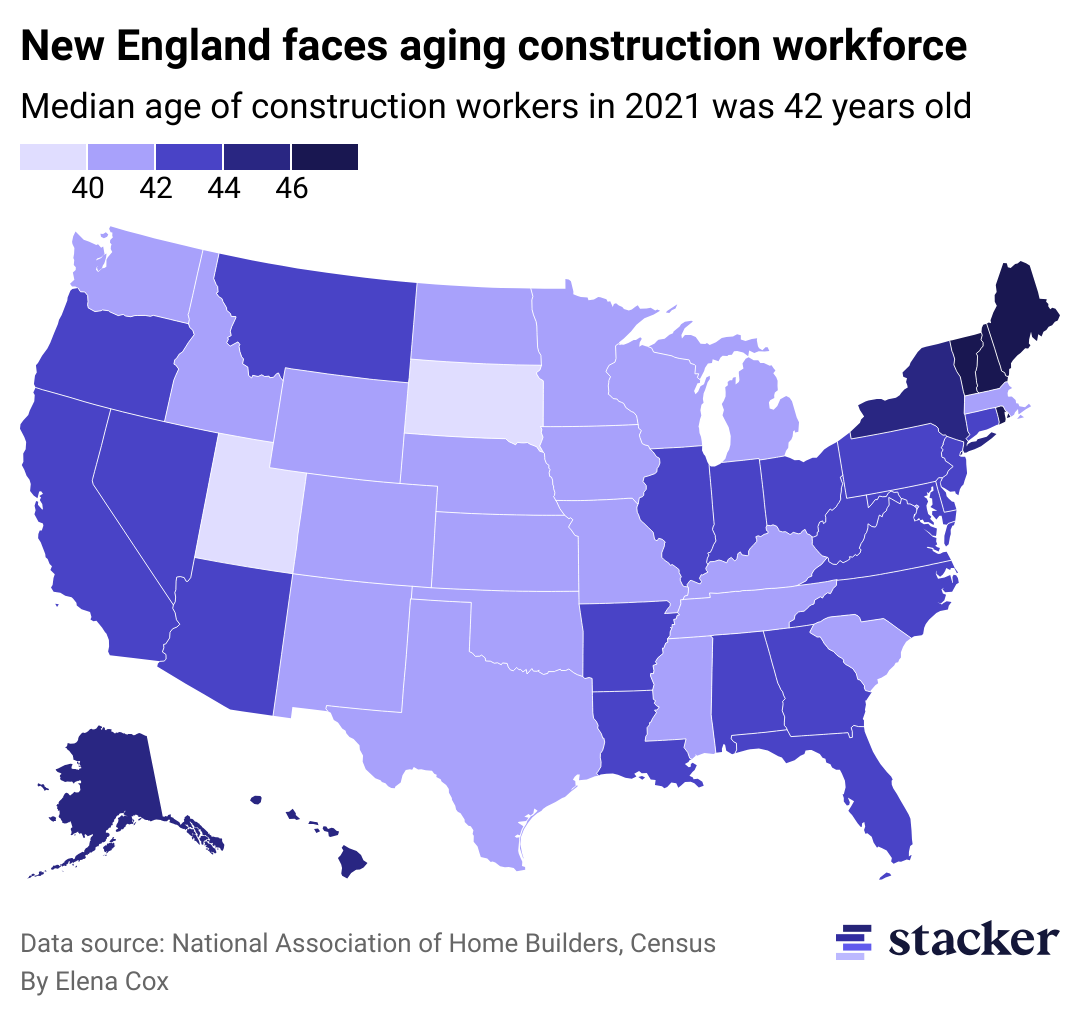

States with the oldest construction workers

In 2021, the median age of someone working in the construction industry was 42, one year older than the overall workforce. In states such as Maine and Vermont, that number was closer to 47.

Part of this is because homebuilders have been focusing on building in the South over the past decade, so that’s where the jobs are. But the other reason is fewer internationally born workers, who also tend to skew younger, are moving to these states.

In large states such as New York and California, immigrants make up more than one-third of the construction workforce, compared to just 1% in Maine and New Hampshire.

Slowed immigration takes toll on industry

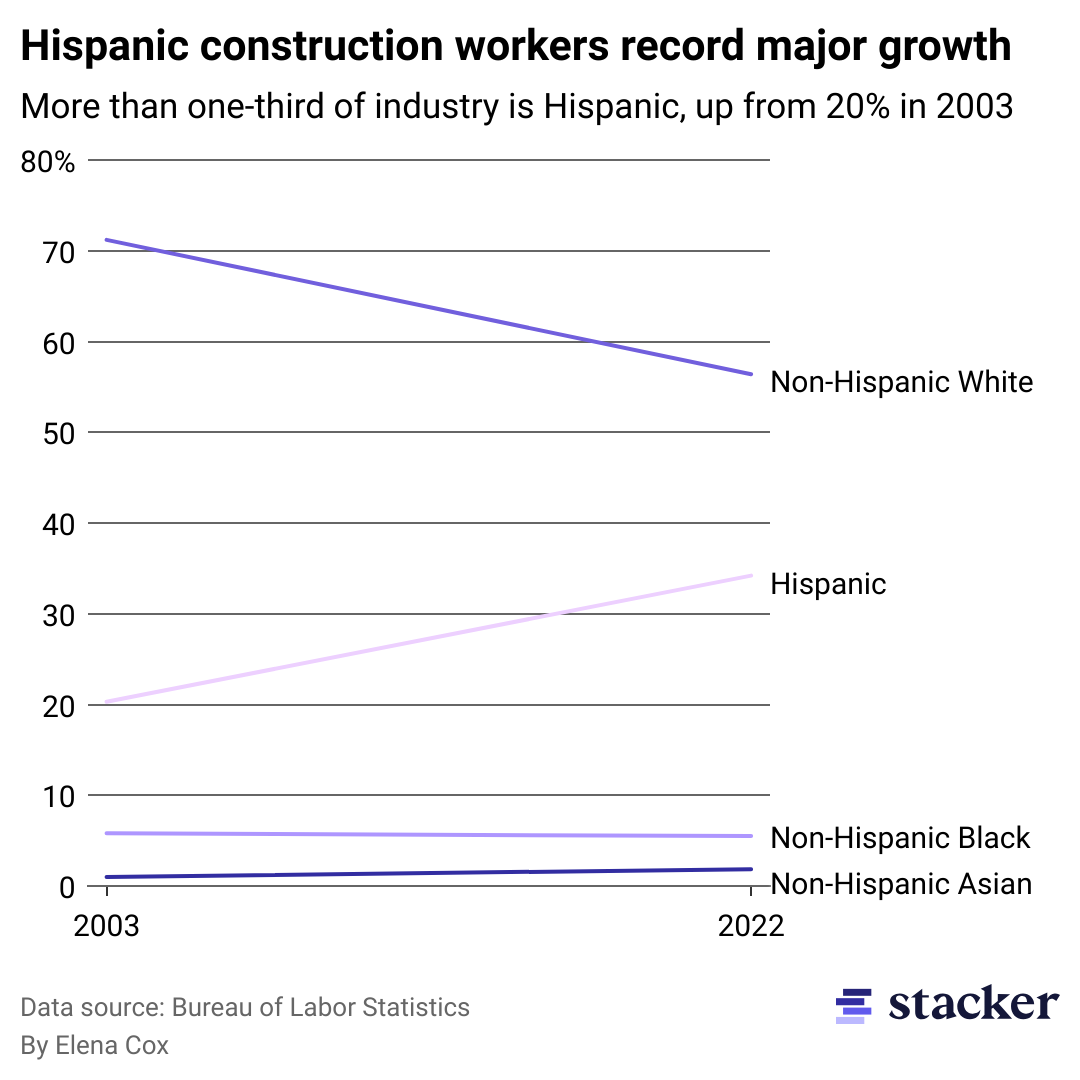

The construction industry has long relied on immigrants to fill positions. Hispanic workers have recorded the largest job gains over the past two decades as the number of people from the Americas entering the U.S. has grown. But that trend has slowed as the COVID-19 pandemic and unfriendly immigration policies decelerated Hispanic people’s relocation to the United States.

“Our industry is 30% immigrant, so with a lower pool of immigrants coming in, it’s hard to fill those gaps,” Brady said.

Career and technical education loses favor

Decreasing immigration is only part of the reason for the labor shortage, though, and a more recent one.

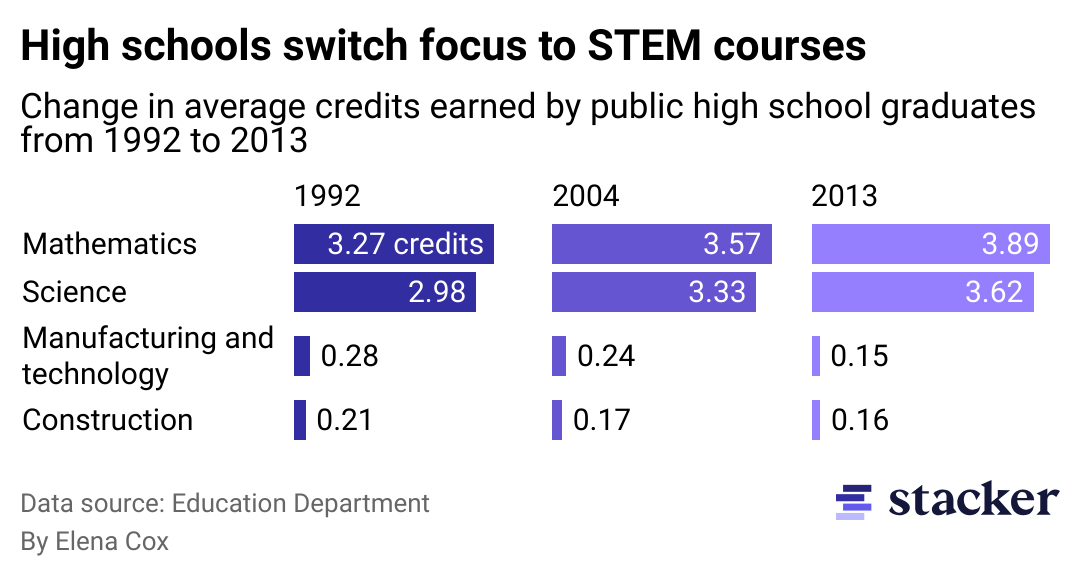

Over the last few decades, people have viewed manual labor as an unsuccessful career path. That, along with the proliferation of computers, caused schools to switch their curricular focus to STEM courses instead of career-focused classes like woodshop.

At the same time, public high schools began to measure success based on the share of students who graduated. By the early 2000s, the No Child Left Behind Act required schools to report and set target high school graduation rates or face sanctions. The government used those metrics to determine how much federal funding schools would receive.

These changes put more young people on a college-bound track, as they took 0.5 fewer credits of career-oriented courses and 1.8 more core academic course credits between 1992 and 2013.

Building the future

Looking ahead, both Brady and Dietz agree the construction worker shortage is a problem that won’t resolve itself.

Both private companies and the government must actively recruit and train young people to enter the workforce, which takes time and money.

That includes reaching out to women and Black Americans, who have long been underrepresented in the industry, and providing on-the-job training or apprenticeship programs. Getting more people interested in construction trades is a significant piece of the puzzle in solving the housing affordability crisis. And at the end of the day, builders need people to be able to buy their products.

If not, Brady said, “We’re going to continue to have inventory shortages and price increases that are taking buyers, especially first-time buyers, out of the market.”

Story editing by Ashleigh Graf. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.